Nonsense Sonatas and Headlong Lyricism:

Interview with Michael Kasper

Michael Kasper is a book artist—Plans for the Night (Benzene, 1987), All Cotton Briefs (Benzene, 1992), The Shapes and Spacing of the Letters (highmoonoon, 2004), etc.—and a translator of, among others, Saint Ghetto of the Loans by Gabriel Pomerand (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2006). His selections (and many of his own translations) comprise Pleasure Editions’ forthcoming release of Paul Colinet’s poetry, The Lamp’s Tales.

When and where did you first come across Paul Colinet, and what drew you to him?

I’d seen his name in histories of Surrealism that I’d been reading on and off, from my college years, and there were a few poems I’d seen, translated by Paul Bowles in an old New Directions Annual, but it wasn’t until I came across Rochelle Ratner’s versions in Bob Heman’s fabulous little magazine Clown War in 1975 that I really connected with Colinet’s work. I was drawn to his fantasy, his wordplay, and his facility with short prose as a genre. More recently, as I’ve been translating other Belgian Surrealist writing, I’ve re-connected. And I’ve discovered that Colinet created verbo-visual pieces in addition to just writing texts, so that’s endeared him to me even more.

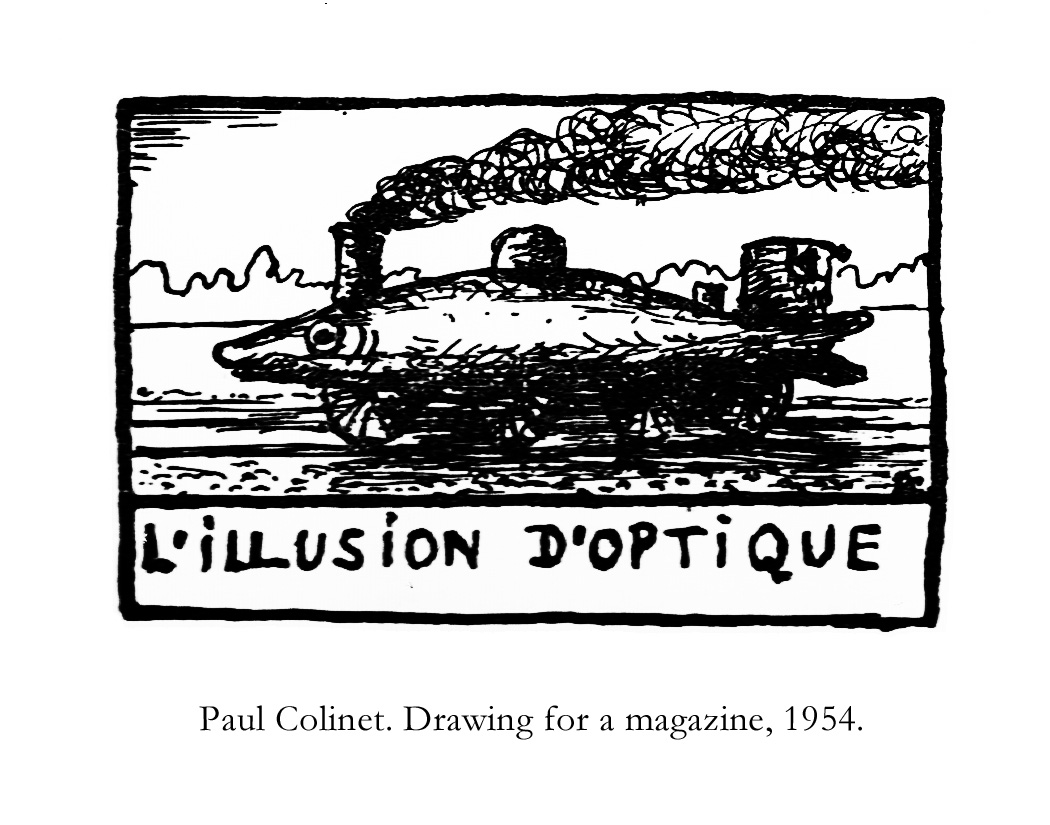

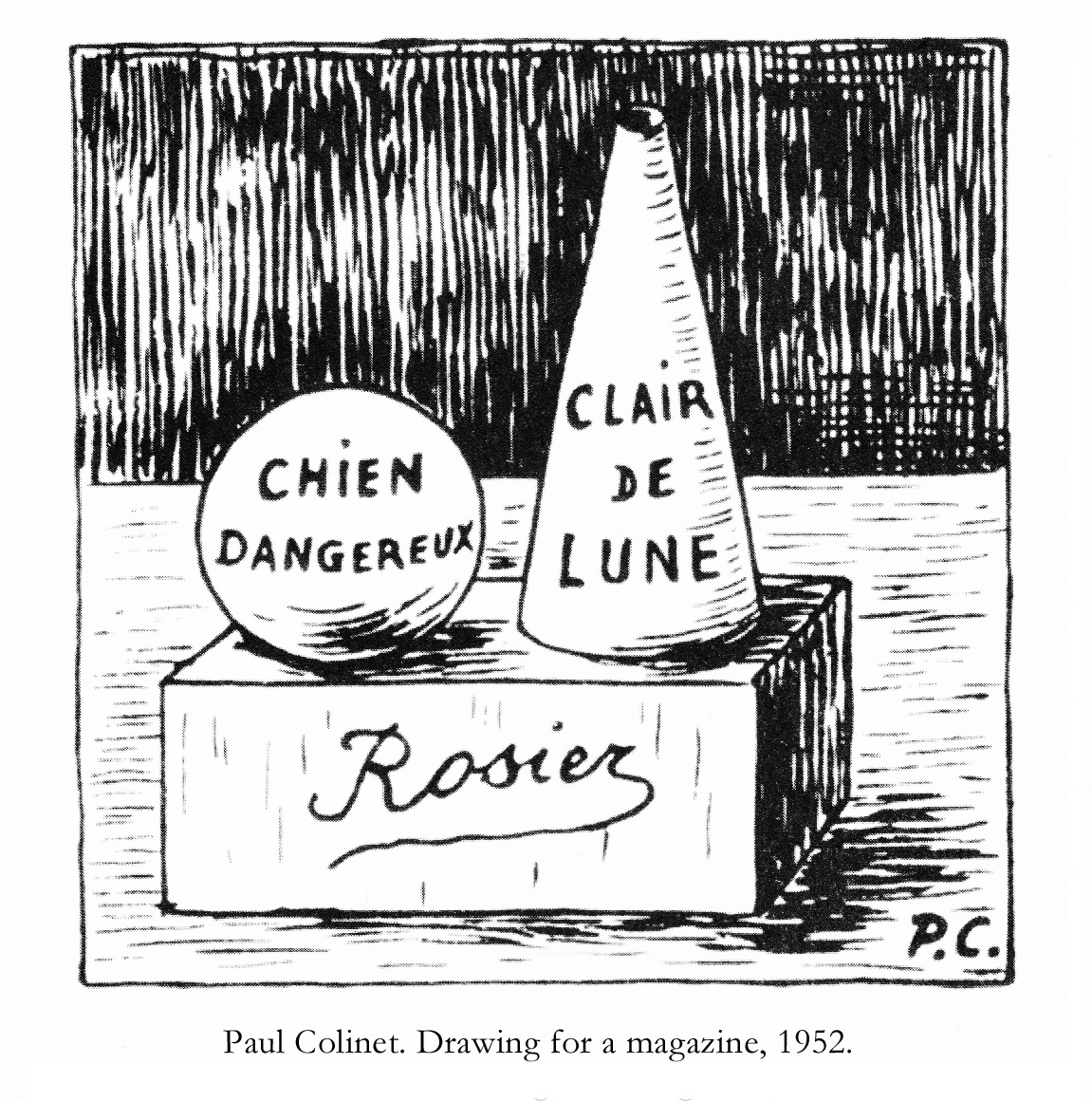

Of course, your own creative work mixes words and pictures. What kind of verbo-visual pieces did Colinet do?

Well, there was a unique (or very limited edition) little artist’s book that’s reproduced in his collected works—Abstractive Treatise on Obeuse, it’s called—that’s coming out in my translation/facsimilization from Ugly Duckling this fall. A sonata of nonsense, charming like all his stuff. Then there was the incredible, hand-drawn, hand-lettered weekly ‘newspaper’ Vendredi (with occasional contributions from his Surrealist friends) that Colinet produced for a while to keep some relations living in Africa up to date. I’ve seen reproductions of scattered pages in secondary sources. And there were collaborations, captioned drawings, done with assorted friends who were visual artists, notably Magritte and the cartoonist Robert Willems, Colinet’s nephew.

Well, there was a unique (or very limited edition) little artist’s book that’s reproduced in his collected works—Abstractive Treatise on Obeuse, it’s called—that’s coming out in my translation/facsimilization from Ugly Duckling this fall. A sonata of nonsense, charming like all his stuff. Then there was the incredible, hand-drawn, hand-lettered weekly ‘newspaper’ Vendredi (with occasional contributions from his Surrealist friends) that Colinet produced for a while to keep some relations living in Africa up to date. I’ve seen reproductions of scattered pages in secondary sources. And there were collaborations, captioned drawings, done with assorted friends who were visual artists, notably Magritte and the cartoonist Robert Willems, Colinet’s nephew.

So Colinet was influenced by visual art. How do you think that played out in his writing? And what were some of his literary influences?

Like other Belgian Surrealist writers, Colinet provided titles for paintings by Magritte. Magritte’s titles are so rich. “The False Mirror.” “The Palace of Curtains.” “The Empire of Light.” “Time Transfixed.” Paul Nougé was probably the first of the fellow members of the Brussels Group to supply Magritte with titles, followed by Louis Scutenaire, and later Colinet. So Colinet, in addition to doing his own visual art, was closely associated with one of the most influential visual artists of his generation. It all shows in his writing, I think, in at least one fairly obvious way: in the richness of his visual descriptions.

I haven’t seen any accounting of Colinet’s literary influences, or an interview in which he mentioned any, but I hear Lautréamont in his headlong lyricism. Lautréamont and other 19th century French prose poets, like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, influenced all the Belgian Surrealists—their provocative stance as well as their inclination to write short prose. Nougé wrote a lot of short essays and anecdotes, Scutenaire specialized in aphorisms, and Colinet was an exquisite prose poet.

![]()

I haven’t seen any accounting of Colinet’s literary influences, or an interview in which he mentioned any, but I hear Lautréamont in his headlong lyricism. Lautréamont and other 19th century French prose poets, like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, influenced all the Belgian Surrealists—their provocative stance as well as their inclination to write short prose. Nougé wrote a lot of short essays and anecdotes, Scutenaire specialized in aphorisms, and Colinet was an exquisite prose poet.

Much of your own writing, as well as the work you’ve translated, consists of prose poetry or short prose. Can you speak to the prose-poem in general, as well as Colinet’s place (and your own) in its history / practice?

Short prose, as I map it, includes prose poetry, newspaper sketches, fables and parables, aphorisms, philosophical fragments, etc... brief prose texts, regardless of the subject, intention, or, for that matter, place of origin... brief texts that share a critical feature: concision, by virtue of which they become conversational, democratic, giving readers an early opportunity to respond. For me, short prose is the quintessential modern literary genre, not only for its democratic manner, but because speed, and short attention spans, have been so central to modern lives. Though short prose, in its many forms, has a long history. Prose poetry, as one category, the category of dense, decorative short prose, dates from mid-19th century France. Colinet is in a direct line of descent from the form’s originators,and I think he’s one of the great practitioners.

As for my own place, um, that would be pompous! Though it did actually come up some decades ago: it was one of the most flattering moments in my so-called career, when Christopher Middleton asked if he could include a piece from my All Cotton Briefs in an anthology that he’d compiled of 100 short prose pieces from Chuang Tzu to the present. I was the present. Unfortunately, securing rights was so bothersome and expensive that no publisher would bite.

As for my own place, um, that would be pompous! Though it did actually come up some decades ago: it was one of the most flattering moments in my so-called career, when Christopher Middleton asked if he could include a piece from my All Cotton Briefs in an anthology that he’d compiled of 100 short prose pieces from Chuang Tzu to the present. I was the present. Unfortunately, securing rights was so bothersome and expensive that no publisher would bite.

Can you speak a little on the milieu of Belgian Surrealism as opposed to the various other Surrealisms of the time?

The Brussels Group formed in the mid 1920s, soon after Breton’s first Manifesto was published in Paris. They knew and shared a lot with their Parisian cousins—a commitment to experiment, to surprise and transgression as artistic strategies, and to personal and political liberty—but they differed on some big aesthetic issues, notably the Unconscious and its corollary, automatic writing, which the Belgians rejected. Also, the Belgians’ activities were much less mediatized than the French group’s, and more episodic, perhaps because most of the Belgian artists had day jobs. René Magritte (forger) and the writer and theorist Paul Nougé (biochemist) emerged as the leading figures in Brussels; others included Marcel Lecomte (secondary school teacher), E.L.T. Mesens (gallerist), Irène Hamoir (secretary), Louis Scutenaire (lawyer), and, in the 1930s, Colinet (municipal civil servant). Their work appeared in their own and in Parisian journals, but most of it wasn’t collected or published in books until the 1950s.

As for other Surrealist movements, I don’t know much about them, other than that they developed around Eastern Europe, in Latin America, in Japan, and each was to some degree distinctive.

As for other Surrealist movements, I don’t know much about them, other than that they developed around Eastern Europe, in Latin America, in Japan, and each was to some degree distinctive.

Can you say a little about Rochelle Ratner’s engagement with Colinet and her translations?

Bob Heman emailed me as follows about how he came to publish her versions of Colinet:

“i had seen other translations of French poets Rochelle had done and asked her if she'd be interested in trying Colinet - years earlier in 1971 (after my friend Flora helped me by transcribing some Colinet longhand while sitting in the big reading room at NYPL) i had approached another friend to possibly translate them, but he thought they'd be too hard to translate - i first saw Colinet in New Directions Annual 14 included in an 80-page anthology of "the poem in prose" edited by Charles Henri Ford - it included 3 pieces by Colinet translated by Paul Bowles (which had originally appeared in the surrealist magazine View) that amazed me.”

I didn’t know Rochelle, though we met once, at a small press book fair, in the 1980s I think; maybe Bob introduced us. She was then fairly well-known, for her own writing and for her involvement in the American Book Review. She died in 2008. I find her translations fluent and faithful, and I tried to make mine consonant. The main challenges in translating Colinet are finding equivalents for his sparkling lexicon, and making his disparate elements coalesce, and, with her excellent English, Rochelle did those things really effectively.

“i had seen other translations of French poets Rochelle had done and asked her if she'd be interested in trying Colinet - years earlier in 1971 (after my friend Flora helped me by transcribing some Colinet longhand while sitting in the big reading room at NYPL) i had approached another friend to possibly translate them, but he thought they'd be too hard to translate - i first saw Colinet in New Directions Annual 14 included in an 80-page anthology of "the poem in prose" edited by Charles Henri Ford - it included 3 pieces by Colinet translated by Paul Bowles (which had originally appeared in the surrealist magazine View) that amazed me.”

I didn’t know Rochelle, though we met once, at a small press book fair, in the 1980s I think; maybe Bob introduced us. She was then fairly well-known, for her own writing and for her involvement in the American Book Review. She died in 2008. I find her translations fluent and faithful, and I tried to make mine consonant. The main challenges in translating Colinet are finding equivalents for his sparkling lexicon, and making his disparate elements coalesce, and, with her excellent English, Rochelle did those things really effectively.

What forthcoming projects are you working on—translations as well as your own work?

I thought I was done with Belgian Surrealism, but a few months ago I was lucky enough to acquire a copy of Nougé’s Subversion des Images, the collection of strange, funny photos and accompanying notes on photography that he produced in the late 1920s. It was finally published a year after Nougé died, in 1968, by the second-generation Belgian Surrealist Marcel Mariën. I think I have to translate it, hoping I can arrange to get the rights...

As for my own stuff, not much of late.

As for my own stuff, not much of late.

We’ve discovered some wonderful authors through your books and conversations with you, from Elena Guro to Gabriel Pomerand. Which authors or artists are you currently excited about?

I’ve been excited to see translations appearing of work by writers previously little represented in English, in particular two authors I consider seminal modernists. Wakefield Press has been publishing Paul Scheerbart, and Black Scat Books has been bringing out Doug Skinner’s Englishing of Alphonse Allais. I’ve also been pleased to see a lot of Alexander Kluge come out from Seagull, though the translations are uneven; Kluge’s fabulous science fiction, Learning Processes with a Deadly Outcome (Duke, 1996) is worth tracking down.